A bright lad, he starts school a year early. Then, continuing to show academic promise, he skips a grade in elementary school.

Everything about the situation, according to Lawrence King, works well.

“Till I got to junior high.”

There, at least two years younger than everybody else, he becomes a target. Smart but immature, he is relentlessly picked on. Chased home after school. Beat up. Bullied.

Even the notion of trying to prop himself up through school sports, always a worthwhile venture, is undone. “I just didn’t have the ability.” So, despite trying out, he fails to make a single squad.

“My self-esteem was nil,” King says. “If it hadn’t been for a loving family, if I didn’t have that support, I could’ve been suicidal. I had a good family at home, but my school life was miserable.”

The boy, understandably, has every reason to dread the next step in his coming of age — high school at Viscount Bennett. Would things get worse? Was that even possible?

In Grade 10, he auditions for the football team. Nope. Then the basketball team. Nope. “The same old scenario.”

The following year, however, there’s a shift when he tries out for the junior boys’ basketball team.

Near the end of camp, there are 14 hopefuls, King remembers. “The coach said, ‘I’m going to put the final 12 names up on the board tomorrow. If you are one of the two that got cut and you think I made a mistake, I want you to come to talk to me.'”

King is pared from the roster. “I was devastated.” So he pleads his case, explaining to the coach that he’s joined the YMCA, that he’s recently purchased his own basketball, that he intends to practise in his spare time. Mulling it over, the coach decides to let King stay. The kid gets his first team jersey — and sleeps with it that night.

By season’s end, King has worked his way into the starting five. “That changed my whole world.”

A world that is only starting to change.

A friend encourages King to join a youth group organized by the United Church. “They were doing a lot of really neat things” — including putting on social events. At one of these gatherings he meets a girl named Helen, who, after a sock hop or two, agrees to be his girlfriend.

“From then on, that was it,” says King, pointing out that he and Helen have been married for 57 years. “She gave me the self-esteem and showed me that I was important.”

Without question, things are looking up for the “original 90-pound weakling” — his description — who, as it turns out, isn’t finished exploring the breadth of his athletic upside.

One of the teachers, as part of gym class, makes the students run two miles. King discovers he can keep pace with the “so-called jocks” — to his surprise and, no doubt, theirs.

“I thought, ‘Man, I’m just as good as these guys,'” he says. “So I decided to get really serious about it.”

King buys a track suit and a pair of sturdy shoes. Daily, he gallops around the block, timing himself. He makes the track team as a distance runner. “I became fanatical.”

Before graduating from high school, he places third in the half-mile at the city championships. “That was my first little victory.” In the open mile the next season, King captures the provincial title in Stettler, smashing the record in the process.

“That got me going.” With distance being no deterrent, King signs up for a 50-mile race in March 1963. One of only four finishers, he prevails. His clocking, a shade more than nine hours, stands as an unofficial record in Canada.

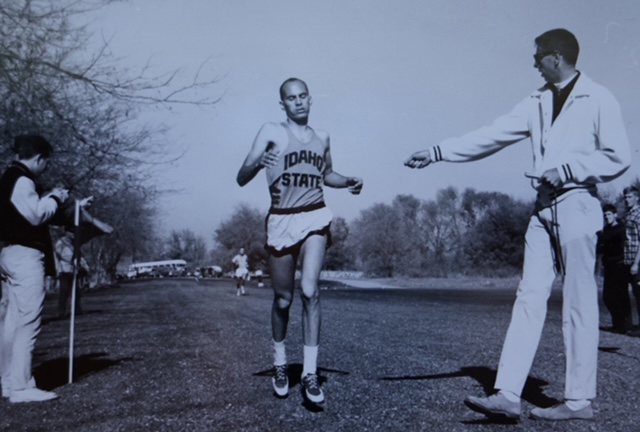

The young man is soon sifting through scholarship offers from Idaho State University, University of Oregon, University of Houston, Southern Illinois University Carbondale. He chooses to go to Pocatello.

“I thought I’d rather be a big fish in a little pond than a little fish in a big pond, so I went to Idaho State,” King explains. “That was the best move that ever happened to me. Thanks to that, I really flourished.”

A four-year letterman in college, he runs the two- and three-mile distances, plus cross-country (establishing a freshman record) and the 3,000-metre steeplechase (becoming the Big Sky Conference champion as a senior). “I thrived.”

Armed with Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Education degrees, King returns to Calgary in 1968 and throws himself into the business of getting even.

No, not with the bullies who nearly destroyed his life, but by squaring his debt of gratitude to mentors and programs that helped to rescue him from a desperate childhood.

As a teacher, King goes on to produce a remarkable career, brimming with dedication and selflessness.

“I had this burning desire to pay back people that made a difference in my life,” he says. “My feeling is that if someone’s done something for you that’s important, the only way to keep it going is to give back, to do the same thing.

“I’ve always wanted to give back in sports to thank coaches for what they did for me. That’s why I coached for 52 years.”

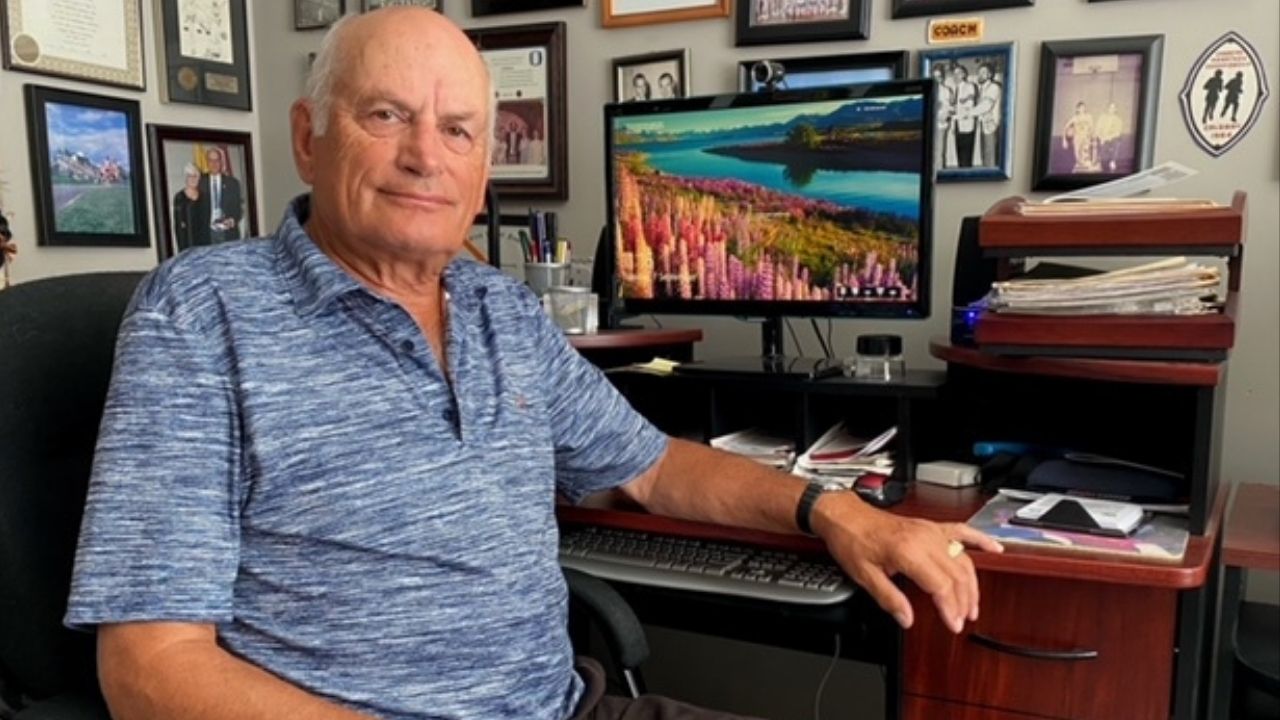

When the subject shifts to his legacy during a recent chat, King endeavours to steer the conversation another direction.

“I’ve been very fortunate in my life,” says the 78-year-old. “But I don’t want you to mention all that. I don’t want to sound like I’m bragging.”

Fair enough. But it’s worth mentioning the basics.

For his efforts, King has been recognized many times, including the prestigious Robert Routledge Award for his service to high school athletics in Alberta. His own name is attached to plenty of honours — such as those for high school track aggregates and outstanding volunteer coaching. And, of course, there happens to be a certain high school gymnasium in the city that bears his name.

By the Calgary Booster Club in 1987, King was named an Honoured Athletic Leader. He’s been a club member for 35 years and, since 1992, he’s served as the awards and scholarship chairman for high school athletics. Topping it off, he was the 2018 Sportsperson of the Year.

King continues to shoulder the role of historian. The Booster Club, over the decades, has hosted 65 award banquets. In his possession are 58 of the programs, meaning he is itching to get his mitts on the other seven. (If anyone happens to have copies of the booklets from 1956, 1959, 1960, 1961, 1963, 1964, 1965, he is eager to know.)

“That’s where the history is,” says King.

His reputation as deep digger is well established.

Shortly after the Calgary Senior High School Athletic Association celebrated its 90th anniversary in 2003, organizers realized they need something special to mark the centennial. The first step was obvious — recruit King.

This is the man who could — and would — write the book on the subject. “They said, ‘You’re the automatic guy,'” he says. “I said I’d think about it. That’s a huge job.”

Agreeing to deliver, King devoted eight years to the project, interviewing difference-makers in the city, scouring the archives at the Glenbow Museum. Quite rightly, he’s proud of the result — the commemorative book, “Tip-Offs, Touchdowns and Tournaments: 100 Years of Excellence.”

King didn’t limit his goodwill to high school affairs and fact-checking perfection on behalf of the Calgary Booster Club.

He was part of the organizing committee for the 1997 World Police and Fire Games. He spent 14 years, 1985-98, as the Special Olympics meet director in Alberta. He has pitched in for golf tournaments, the Calgary Food Bank, Rotary Stampede breakfasts, on and on and on. On his resume, in fact, are more than 80 examples of (non-coaching) volunteering.

But it is King’s commitment to Calgary high school athletics — as a student, athlete, coach, teacher, administrator — that stands out.

“My whole life was changed because of it,” he says. “It’s been a major part of my life.”

In 1968, King got his first job at brand-new Central Memorial and immediately snatched the coaching reins of the cross-country, football, basketball, golf, and track and field teams. From there, he transferred to Western Canada, then moved to the Calgary Board of Education’s headquarters. He worked at Ernest Morrow and James Fowler schools, too.

Every step of the way, he stayed well immersed, beyond the classrooms and board rooms. He continued to coach — track and basketball had been his specialties — after he retired as a teacher in January 2003.

The night held in his honour at Henry Wise Wood, the final stop of his professional career, will not be soon forgotten.

For starters, King noticed a wrapped package, long and narrow, at the front of the gym — and that got him thinking. At the school, he’d been in charge of the parking lot. “It was a horror show. Always a hassle.” So the gift, he guessed, was a joking reference to that sentiment. Remembering, he laughs. “I thought they were going to give me my own parking spot — the Lawrence King Parking Spot.”

Instead, they called him up and informed him of the latest honour. “Lawrence King Gymnasium,” read the laminated sign, which, once unwrapped, would be affixed to a spot above the main doors.

“Really cool,” he says. “It was really nice.”

Two other presentations touched him, too.

One was a charcoal drawing of himself, created by a student, who, three years earlier, had been like “Dennis the Menace.” After suspending the boy a couple of times, King decided to mentor him. “I started to see some possibilities. All of a sudden, he started to turn things around and he became a pretty darn nice kid, right? In Grade 12, he wasn’t getting kicked out of class anymore, and he would come to see me just because he wanted to talk about something.”

King didn’t expect the artistic piece. “I mean, that was really special.”

Also resonating that night had been a poem, written and read by a student, who, once upon a time, he’d placed on his senior girls’ basketball team because of her splendid attitude. “I said, ‘I can’t guarantee I’ll get you into every game.’ That was her Grade 11 year and she did get a lot better. By the end of the year, she was playing a lot.”

But having a poem penned in his honour? That gesture, too, caught him off guard.

“It was beautiful,” says King. “She said what an impact I had on her life — that I made her feel like she was important.”

Now, nearly 20 years later, the drawing and the poem are prominently displayed on the office walls of his Lake Chaparral home.

This past winter, he received an email from one of his former track athletes at Western Canada High School. The sender, coached by King more than 40 years ago, had recently suffered an accident, crushing his hip. Stuck in a hospital bed, he began to take stock of his life. Coach King immediately came to mind. “I just wanted to tell you thank you very much,” he wrote to King.

Over the years, King has even been asked to give toasts at the weddings of his former athletes.

“What’s really neat, with kids, you really never know if you made an impact or not,” he says, “but some kids actually come and tell you that.

“That’s why you’re a teacher, that’s why you’re a coach.”

No surprise, King, as a boy, had been no different. Appreciative then — and now — of his own mentors. Such as the encouragement of basketball coach Ken Cooper (who, after originally cutting the kid, relented); the guidance of phys-ed teacher John Semkuley (who laid out the potential of a future in running); the tutelage of track coach Doug Kyle (who helped the skinny lad land a college scholarship).

In his acceptance speech at the 2018 Sportsperson of the Year banquet, King also thanked Father Jim Whelihan, Bob Freeze, John Mayell, Bill Phillips, Stan Jaycock, Deak Cassidy, Tom Humphrey, Stan Schwartz, Alf Fischer, Frank Sissons, Carol Kyle, Joe Massey. He added: “There is a familiar quote that says, ‘I am a part of all that I have met.'”

His gratitude is unmistakable. Still.

With the guidance of others, King had been able to do an about-face — the target of bullies became one of the city’s most decorated and highly respected athletic influencers.

“I was nothing until I got to high school — I was a nobody,” says King. “I love sports. I’ve always been a sports fan, but it’s the high school part that’s important to me because that had the biggest impact on my life.”