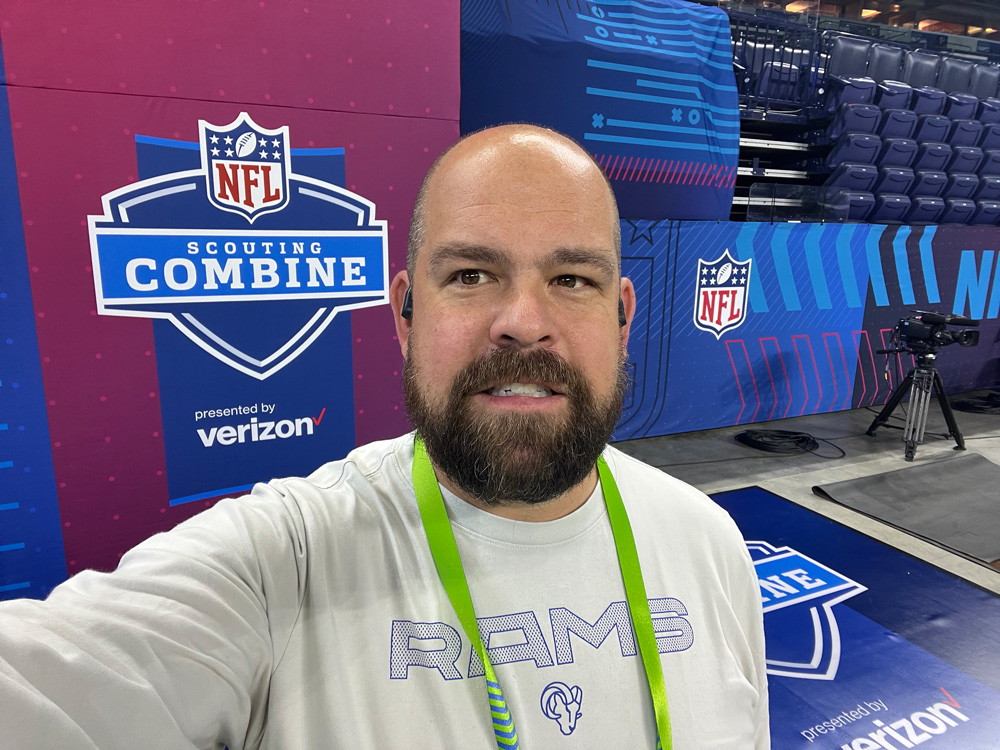

Photos courtesy of Dan Dmytrisin.

Within reach of professional football’s peak, the Calgarian keeps his head down, his wits about him, his focus sharp.

Because there is still work to do. The Super Bowl — this particular Super Bowl — is something else. Wickedly close. Hotly contested.

And not over. Not by a long shot.

“Pretty wild,” said Dan Dmytrisin, video director of the Los Angeles Rams. “If you think about it, the game went right down to the wire.”

Inside the two-minute warning, the Rams are trailing, but, driving, they shove ahead by three points. The football then goes back into the capable mitts of Cincinnati Bengals quarterback Joe Burrow — but his comeback hopes are quickly dashed by superstar defender Aaron Donald. Game over.

“It was just like, ‘Wow.'” But given Dmytrisin’s immediate surroundings — SoFi Stadium’s eye-in-the-sky booth shared by video staffers from both the Rams and Bengals, plus network-television workers — the momentous occasion, a 23-20 victory, passes with only marginal exuberance.

Dmytrisin knows that his Cincinnati counterpart has been in the NFL for 30 years, that this is his first Super Bowl appearance, meaning it is not the time and place for a raucous display of emotion. He settles for “a fist-pump with a really big smile.”

Then it’s quickly back to the typical post-game routine. Dmytrisin breaks down his equipment, packs it all up. Escorted by security, he marches directly to the emergency-exit stairs, which, much faster than the elevator, delivers him to event level.

Once down on the field, he dumps his gear on the sidelines and allows the atmosphere — and the still-flying confetti — to wash over him.

Dmytrisin is a Super Bowl champion.

On stage, head coach Sean McVay, general manager Les Snead, and team owner Stan Kroenke are receiving the Vince Lombardi Trophy. Jubilant players and thrilled fans roar their approval.

“What you see on TV, to be there on the field is absolutely surreal,” said Dmytrisin. “Super Bowl is typically one of the those things where you get together with friends and family to watch it on TV, taking it in, taking in the halftime show, watching the commercials, eating too much food, drinking a little bit too much.

“To be actually there? As one of the two participants in that game? It’s pretty surreal.”

Eventually, the celebration shifts, from the turf to the Rams’ locker-room, where champagne bottles are uncorked, cigars are puffed, beverages are guzzled, backs are slapped. A few hours of revelry later, everyone is bussed back to the team hotel, before heading over to Hawthorne Municipal Airport for an exclusive hangar party.

“At that point, if you include preseason, that’s 24 games in 27 weeks — so more than six months you’re spending with these people, day in and day out. You’re together with these people a lot,” said Dmytrisin. “You’re at the pinnacle of your profession. To be there is pretty phenomenal.”

In everyone’s case, that is true — but especially Dmytrisin’s. Consider his DIY ascent:

Start in the sport — right guard for the Sir Winston Churchill High School Bulldogs.

Introduction to professional football — two seasons with the Calgary Stampeders.

Current status — video director of the best club in the best football league in the world.

“It’s awesome,” said Ross Folan, long-time director of video operations for the Stamps. “Sir Winston Churchill has a Super Bowl winner. Calgary has a Super Bowl winner. Dan is born and raised in Calgary, he helped us out here, and forged a path to take him to the top.”

Right to the very top.

Enrolling in biological sciences at the University of Calgary in 2000, with the intent of becoming an anesthesiologist, Dmytrisin had a change of heart after two years.

“It wasn’t quite for me. So I bounced around doing odd jobs.”

Including a stint with Cine Audio Visual, doing system design and installation work. Because one of the company’s clients was the Stamps, he’d often end up at McMahon Stadium. There, his contact was Folan, and they struck up a friendship.

“Dan said, ‘This stuff’s really interesting. I’d like to know a little bit more about it,'” recalled Folan. “So we’d take an extra 10 minutes here or there when he had to come by. That’s kind of how it happened.”

In May 2004, Dmytrisin was hired as the Stamps’ assistant video co-ordinator. He embraced the role, absorbing more than the knack of filming practice and cutting tape for coaches.

Sport at that level, in a hurry, taught him to appreciate the value of teamwork and the upside of goal-oriented process.

“You’re kind of one piece in the puzzle, basically, one cog in the machine, and it’s sometimes hard to see the end result,” Dmytrisin said. “(With the Stamps) I could be part of something public and something people look up to. It’s sports entertainment and that brings joy to so many people. Looking up in the stands, you see the kids so excited to see their superheroes. And to be able to contribute to the success on the field, that’s pretty special.”

If two years at the U of C left him wondering about his professional track, two years with the Stamps revealed an appealing direction. This was turning into a career, one with a goal. “To be a video director at a big-time college program.”

Thanks to Folan’s connections, Dmytrisin landed a scholarship at Northern Arizona University. In Flagstaff, the young man handled video duties for the football team and graduated with a degree in computer information systems in 2008.

That experience led to him to USC, which he helped to prepare for the 2009 Rose Bowl. He returned the following season as an intern. But, offered a job as technical account manager for DV Sport, a digital company, he was on the move once again, this time to Atlanta. His clients included Georgia Tech, Auburn University, Atlanta Falcons, Seattle Seahawks, Arizona Cardinals.

In 2011, Dmytrisin to returned to USC as video systems administrator. He fortified his football reputation and, taking advantage of free tuition, completed a master’s degree in cyber security engineering in 2019.

Shortly thereafter, the Rams reached out. They wanted him to take the reins of their video department.

This, understandably, prompted plenty of discussion in the Dmytrisin household, with his wife Meredith, with others familiar with the situation.

“At that point, I’d been with USC for nine years, so it was very comfortable,” he said, “but I looked at it as, ‘This is a new challenge. Not every day will you get an opportunity to work for an NFL organization.'”

Making the leap, he started work on the Monday — March 16, 2020. This was to be a career-making day for Dmytrisin, who drove to the Rams’ administration office in Agoura Hills and strode up to the entrance.

“There was a note on the door — and basically it said, ‘We are closed till further notice,'” he said. “My onboarding process was in the heat of the (COVID) pandemic and quarantine and working from home. So it was a little nerve-racking.

“And that’s when I started with the organization.”

Of course, Dmytrisin has settled nicely into the position, two full seasons now under his belt.

Asked to boil down his job description, he replies: “In a nutshell, any video that our coaches, players, scouts watch runs through our department.”

His group — seven people, including himself and four other full-timers — represents one of the NFL’s bigger staffs, but “given our responsibilities throughout the week …”

Dmytrisin’s duties include processing video for every regular-season NFL game and hundreds of college games (1,900 and counting this year). He is also in charge of sideline tablets, providing in-game content and ensuring the devices function properly.

“An NFL game is 170 to 190 plays,” he said. “So you’re staying focused, you’re in the moment, making sure you don’t miss anything, making sure that you and your team are locked in. By the end of it, you’re just mentally drained.”

In professional sport, demands are high and hours are long. Weekends, evenings, holidays are often spoken for.

Even in the days following the Super Bowl triumph, Dmytrisin is kept hopping.

Especially for a program as sound as the Rams’, there is going to be personnel turnover. Defensive and offensive co-ordinators being lured away, for instance. “Because everyone wants to be successful, they start poaching your staff,” Dmytrisin said. “With that — coaches leaving, coaches coming — and getting them onboard, and then the timing with the combine.”

Yes, the NFL’s scouting combine, which ate up a full week in early March as the top college prospects paraded through Lucas Oil Stadium in Indianapolis.

The draft is slated for April, meaning extensive preparations. Plus, there are seasonal reviews and free agency assessments. Voluntary offseason-training programs carry clubs into June. Training camps open in July.

“I will try to take a couple weeks off … but there’s always stuff,” said Dmytrisin. “People look at football as three hours of entertainment on a Saturday or a Sunday, but there’s six days of preparation that go into those three hours.”

Dmytrisin laughs, probably because he knows what he’s about to say might sound strange — but appearing in the Super Bowl cost his organization valuable preparation time.

“We’re definitely a little bit behind the 8-ball,” he said. “We’re regrouping to have the best NFL team for 2022. In terms of changing anything, we’re trying to stay grounded, stay in the moment, enjoy what we accomplished.

“Unfortunately, we’re on to the next season already.”

Which seems crazy. The guy’s barely had time to respond to his congratulatory texts.

After ending up on the winning side of that dramatic showdown last month, Dmytrisin’s phone got crammed with more than a hundred messages. “For me, that’s a lot — I can’t even imagine what Coach McVay’s phone was like,” he said, chuckling. “But for me, it was quite a shock, but it was cool to hear from people.”

He points out that the Super Bowl is broadcast to 180 countries. “So whether you’re close friends with someone or not, they’re watching you do your job.”

And, for Dmytrisin, it appears to be a job well done — which comes as no surprise to Folan. The quality of his friend’s contributions speaks for itself. Always has.

“Wherever he wanted to go with his work ethic and his innovation, whatever he applied himself to, he would’ve been successful,” said Folan. “And it’s all self-made … his computer knowledge, his football knowledge. He just worked hard. Always learning, always innovating.

“Everywhere he went, he just did the job and did it well.”

Dmytrisin is sharp — a born problem-solver, an elite trouble-shooter. Someone who’s methodical in their approach. But the old offensive lineman from Winston Churchill is also an appreciative sort. There is a sentimental side. He collects his game passes, all of them. And before every opening kickoff — wherever the Rams happen to be playing — he snaps a selfie, which he texts to his wife and to his mom.

So, of course, he’s proud of his Super Bowl success.

“Absolutely. Sometimes it’s hard — you’re buried in the day to day,” said Dmytrisin, who turns 40 next month. “But to be able to contribute to an organization’s success … if you think about what we had to overcome the past two years — with COVID protocols, restrictions within the NFL, having an outbreak where a game got pushed, dealing with supply-chain issues, dealing with weather, all that stuff.

“When you step back and look at it, it’s been a challenge, but it’s also been probably the most rewarding experience I’ve been a part of, outside of getting married and the birth of our son (William).”