Each year on April 15th, Major League Baseball (MLB) honours the legacy of Jackie Robinson by having all players, coaches and on-field staff wear his No. 42 during games on that date. The infielder broke baseball’s colour barrier on April 15, 1947 and Jackie Robinson Day celebrates his life and achievements.

Robinson made a memorable visit to Calgary in 1955. Here is the story of his first Canadian speaking engagement …

It’s not quite as iconic as the Brooklyn Dodgers hat that we associate with Jackie Robinson.

But for one night anyway, Robinson was kind enough to trade in his baseball cap for a white cowboy hat.

Just two months after winning his first and only World Series – which was also the first and only title the Brooklyn Dodgers captured – Robinson found himself in Calgary and, well, he was introduced to a folksy Alberta tradition.

Attending an awards banquet hosted by the Western Division of the Canadian Council of Christians and Jews, Robinson stood at a podium before a crowd of 200 people and received the white cowboy hat from Calgary MLA Art Smith, a founding member of the Calgary Booster Club.

At that point, the white-hatting of guests to the city was a relatively new greeting for celebrities and dignitaries – a symbol of Western hospitality started by Don MacKay after he became Calgary’s mayor in 1950 – but Robinson appeared to enjoy the ceremony, even if the hat itself seemed to sit atop his head rather than fit snugly.

The first African-American to play Major League Baseball in the modern era, Robinson was enjoying his championship off-season and was preparing to enter his 10th and final year with the Dodgers when he arrived in Calgary on Dec. 7, 1955.

“Certainly, I’d like to finish my playing career with the Dodgers,” the 1949 National League MVP told the Calgary Herald.

“They have been, and always will be, my team. But I’m in a fortunate spot. I don’t have to play anymore unless I want to. And I won’t play for any team in the American League unless the offer is extremely attractive. It wouldn’t be worth uprooting my family for just a year.”

Added Robinson: “Not that I want to quit playing. I still have another good year of baseball left and I know that I can help any club. It would be nice to complete 10 years in the majors, but it will have to be on my terms.”

In order to make his Alberta visit happen, Robinson had to cut short his appearance at a dinner party the previous night – an awards presentation honouring his Dodger teammate Don Newcombe and heavyweight boxing champion Rocky Marciano.

The 37-year-old’s arrival in Cowtown was front-page news and, while the guest list may have done little to impress a New York crowd, it included many prominent Western Canadians, such as medical pioneer Dr. David Baltzan, of Saskatoon, who was presented with a human relations award from Max Bell, publisher of The Albertan newspaper.

Robinson played for the Montreal Royals in 1946, but his five-day trip to Calgary marked his first speaking engagement in Canada and the first time he visited Western Canada.

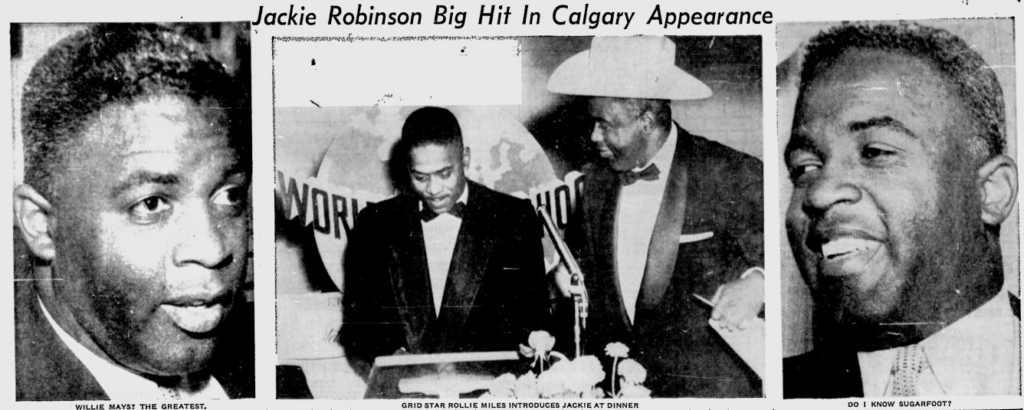

Rollie Miles, a Canadian Football Hall of Famer with the Edmonton Eskimos, provided the introduction to Robinson at the banquet, which was also attended by Calgary Stampeder great Ezzrett “Sugarfoot” Anderson.

Robinson and Anderson met in the 1940s and played football together in the Pacific Coast Football League. They remained friends over the years and Robinson stayed at Anderson’s house during his Alberta visit.

“The Negro race has come a long way in the last 10 years, but it hasn’t come alone. Organizations like the Council of Christians and Jews have made the way easier by 100-fold,” Robinson told those in attendance at the Al-San Club.

“We must judge people by what they can do as individuals. When this is accepted, we will have no problems. After all, we can’t lead the world, if we can’t lead ourselves.”

Calgary Herald journalist Johnny Hopkins praised Robinson’s speech, reporting “he does speak with a sincerity that hits home. He has an excellent voice, knows his subject and uses an off-beat delivery that never becomes tedious.”

The day after his speaking engagement in downtown Calgary, Robinson attended a two-hour press conference, where he spoke on a wide range of topics, from baseball to politics.

Gorde Hunter, sports editor of the Herald at the time, spoke with Robinson about the relationship he had with Branch Rickey, the president and general manager of the Dodgers who helped the infielder break baseball’s colour barrier.

Robinson, whose jersey number 42 has since been retired by MLB, told reporters that Rickey gave him a two-year gag order that prohibited him from fighting back against racial taunts and slurs. But after that, the former UCLA track, basketball, football and baseball star was free to speak his mind.

“I lived a lie for two years,” Robinson told the media.

“Mr. Rickey schooled me on how to meet all situations. He watched me close during those two years and then he came to me and said, ‘Jack, you’re on your own now. Do what you think is right.’”

For Robinson, that meant speaking out against the racial abuse he had endured.

“I had to speak my mind,” Robinson was quoted as saying in Hunter’s ‘One Man’s Opinion’ column in the Dec. 8, 1955 edition of the Herald.

“It doesn’t matter to me what people think of what I say. As long as I know within myself that I’m right, I’ll continue to speak my piece. If I’m wrong, I’ll readily admit it.”

Hunter was impressed by Robinson’s willingness to answer all questions directed his way and noted that “no comment” was not in his vocabulary.

With his speaking engagement done and his media obligations fulfilled, Robinson had a few days to relax and hang out with his good friend Sugarfoot, who had recently retired from the Canadian Football League.

During the downtime, Sugarfoot showed off his successful Royalite gas station, a new source of income for the popular athlete, who also worked as a Calgary radio show host and appeared in 32 movies alongside such acting legends as Gregory Peck, Lee Marvin, Gene Hackman and Shirley Temple.

Robinson appeared at the gas station two days in a row, which caused a buzz and resulted in long lineups of motorists hoping to catch a glimpse of the baseball star.

After gassing up, Sugarfoot and Robinson took a road trip to Banff and Lake Louise, where the two swapped tales about their respective sporting careers.

A longer version of this story was originally posted on the Alberta Dugout Stories website. This article has been re-published here with the author’s permission.