Photos Courtesy of Todd Korol and Lynda Kiejko.

One morning, Dad turns to his children and explains that he needs some help in the basement.

Beyond that, plans are vague.

No matter. Lynda, 11, and Dorothy, 13, agree to pitch in. So Bill Hare and his daughters roll up their sleeves and head downstairs. For hours at their house in Namao, Alta., they drag around boxes and shove aside bookcases.

Sweaty work complete, vision satisfied, Bill assesses his tired little helpers, who are a little mystified by the undertaking, and says, “Now that we’ve got an air-pistol range, would you like to try air pistol?”

Now the basement’s re-arrangement begins to make sense.

Because the girls know Dad has guns. They know he practises. They know he competed at the Commonwealth Games because there is a gold medal around some place. But the fact that Bill, a reverend of the United Church, has gone three times to the Olympics is lost on them. And certainly they are unaware that, in some circles, their father is known as the “Pistol-Packing Preacher.”

But especially captivating to the kids that day is the chance to try something brand new. And Dad, thankfully, is so …

“Patient,” said Lynda, with a laugh.

Recalling her first crack at shooting — this is 30 years ago — she chuckles, claiming that it took her eight shots, from 10 metres, to even hit the paper target. “It’s funny now to think back.”

These days when Lynda introduces youngsters to the sport, the backbone of which is hard-won precision, there is sometimes disappointment. “And I’m like, ‘No, no, no.'” Because she knows firsthand what it is to be truly bad.

Light bulbs, during the early days, got blown to bits. “It was disastrous. Shots were everywhere.”

Perhaps understandably in Lynda’s case.

Because she was a southpaw trying to get the hang of shooting right-handed with a right-handed gun. This ordeal went on for weeks, with precious little progress. Finally, Dad did the right thing.

“His heart broke a little bit,” said Lynda, “because he literally sawed a couple of very expensive grips in half and mashed them together to make a left-handed grip.” On the first day aiming as a lefty, her scores jumped significantly.

With his girls well schooled in the basics, Bill took a step back. “He just let us go at it, let us try it, let us enjoy it.”

At that stage, Lynda had been getting a taste of a number of sports — such as volleyball, basketball, badminton — with so-so traction. And asthma cut short her cross-country-running aspirations. “Pick a tree, I’m probably allergic to it.”

This gun thing, though, was appealing.

Looking back, Lynda said, “Shooting sports helped propel me forward, keep me connected, and made me feel that I could excel at something. That was really rewarding through the challenging times — the adolescent years.”

No surprise, given the hours invested in the basement range, the kids got better. They embraced the challenge.

“Dad would let us figure out things on our own … he never forced us,” said Lynda. “It was never, ‘OK, it’s 3 o’clock. You better go downstairs and do your training.’ He completely left it up to us — ‘If you want to do it, do it. If you don’t, don’t. Your success is in your hands. You can ask me if you need help.'”

They asked. He coached. They improved. He drove.

Soon, on a regular basis, the family was making the three-hour trip from Namao to camps held at the Calgary Rifle & Pistol Club. A few years later when the Hares relocated to Irricana, Alta., 45 minutes northwest of the city, the trek to the range was much shorter — and much more frequent.

Shooting had struck a chord. As a pastime, it ticked every box for Lynda.

“I didn’t have anyone else relying on me,” she said. “It wasn’t a team sport where you were waiting for someone to pass to you and if you missed it you felt really, really bad about it. Or it wasn’t like a race where everyone always passes you and you always come in last, which is kind of what my races were like.

“It was something where you could just be in your own bubble and evaluate your performance against yourself.

“It was really, really encouraging that I could define my own success.”

Of course, there are other ways to define success.

Such as:

- Bill Hare competing at three straight Olympic Games — 1964 in Tokyo, 1968 in Mexico City, 1972 in Munich.

- Dorothy Hare shooting at the 2012 London Games.

- Lynda Hare (now Kiejko) qualifying for the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro. And she just got back from Tokyo where she’d been part of the field at the 2020 Summer Games.

Toted up — one family, six appearances at the Olympics.

“How cool is that? It’s pretty amazing to have the legacy that we do,” said Lynda. “We got to share this amazing passion with our dad. It was incredible. He was like a superstar to us.”

Prior to the trials for the Tokyo Olympics, Lynda was rooting around in the garage at her family’s home in Queensland, a neighbourhood in southeast Calgary.

“I was looking for something … I can’t even tell you now what now.”

Churning through piles of stuff, she uncovered a medallion. Which, upon closer inspection, turned out to be a keepsake her dad brought back from the 1964 Olympics — in Tokyo.

Given her own aspirations, including the exact same destination, it was a stirring find.

“I was just like, ‘You’ve got to be joking me,'” said Lynda. “This has no business being where I found it. It had obviously been in there since my dad passed away 15 years ago — and here it is.”

Now secured to the key that opens her gun-box lock, how can that medallion be considered anything but a good-luck charm? After all, it ended up seeing her through the trials and all the way to Tokyo — where, believe it or not, the shooting was contested at the Asaka Shooting Range, the venue where the Pistol-Packing Preacher had taken aim 57 years earlier.

“Just a little reminder that I’m sharing something very unique in our family,” said Lynda. “I get to be somewhere my dad was. Although I could walk in his footsteps, it’s almost like I’m making my own footsteps beside his.”

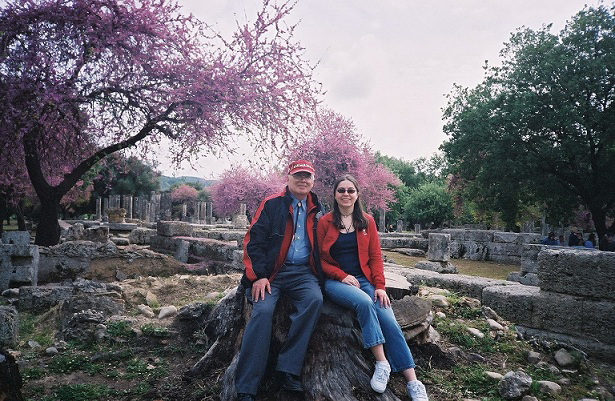

For a 2004 World Cup event in Athens, Bill, as an international federation delegate, travelled to Athens. Lynda, at the last minute, was invited to compete. Rushing around to make arrangements, she reached Greece, exhausted. There, her dad informed her that he had planned out a little junket for them — the next day. She griped, insisting that her jet-lag was too much.

Somehow he changed her mind and, in the morning, they were on a bus bound for Olympia. Lynda will never forget standing — alongside her dad — on the finish line at the original Olympic Stadium.

“An incredible memory that I will cherish for my entire life,” she said. “I can still see the look on his face — you could tell in his eyes the glee and the joy he had from being there, how much this trip and that opportunity and that moment meant to him. My dad passed away within a year of that trip.”

Lynda has shared the stage with Dorothy, too.

Twice at the Commonwealth Games, they represented Canada together. In 2010 at Delhi, India, the sisters earned bronze in the air-pistol 10-metre pairs event.

Of course, being elite shooters in Canada, they’ve also gone head to head — most notably in the lead-up to the London Olympics. Lynda and Dorothy were two of three shooters lined up at the Calgary Rifle & Pistol Club — with one spot up for grabs.

“Tough? Holy cow,” said Lynda. “I was partly rooting for her, but, at the same time, I still wanted to put down my best performance.”

Nevertheless, Dorothy edged her little sister.

“It still stung a little bit,” said Lynda. “I could’ve been bitter, but instead I chose to be excited and enthusiastic for my sister because she was going to be accomplishing a dream that both of us had had since we were kids.”

With Dorothy’s coach unable to travel, Lynda offered her services. So, in the end, they both travelled to the 2012 Summer Games, a meaningful exposure for Lynda.

“One of the biggest catalysts for me making the 2016 team,” she said. “I realized what I was missing from my own sports experience.”

In late-July, Lynda represented Canada in Tokyo, finishing 47th in the women’s 10-metre air pistol and 41st in the women’s 25-metre pistol.

Barely two weeks later, she was shooting at the Alberta championships in Calgary.

“How weird did that seem?” she said. “Coming back from the Olympics and, all of a sudden, I’ve got provincials. Kind of the reverse of things. So I got right back in the saddle.”

Because no matter the stakes — Olympic glory or Alberta baubles or minute improvements while shooting solo — this is where Lynda feels at home. Standing in sport-specific shoes and staring through customized glasses, left arm outstretched, target awaiting.

“I love going to the range, I love squeezing the trigger and having that control over one thing,” said Lynda. “Sometimes you get wound up in the emotion and the expectation to succeed, the push and the drive, the overwhelmingness of everything … but when there’s no expectation and you just get to go because you want to go? It’s so rewarding.”

Time on the range is never taken for granted.

Lynda and husband Kevin Kiejko have three children — Olivia, 7, Faye, 4, Logan, 2. And, as a civil engineer, there’s her job at AltaLink, where she’s worked for 17 years.

So she relishes time on the range.

“It reminds me why I’m still doing it, why I’m still competing,” she said, “why I’ve re-arranged my life … and decided that we’re going to push off potential retirement for who knows how long.”

By now, she must be a master of time management. That makes Linda laugh. “Hardly.”

She counters by saying she’s a master of asking for help. Not unrelated, she adds that Kevin is the “greatest husband of all time” — no disrespect any of the other spouses out there. “But I’m pretty sure I’m the luckiest.”

And the one whose input carries the most weight.

While others may hint to Lynda that her schedule seems a tad overboard, it’s Kevin’s opinion that matters. “He’s the one who gets to say I’m crossing my own crazy line,” said Lynda. “He’s usually right, so we find a new plan and we balance things out as best we can.”

Including expenses.

In the year leading up to the 2020 Olympics, Lynda was working half-time. Now she’s nearing 80 per cent. Every bit helps, considering shooting gear.

She went to Tokyo with an pistol that had air cylinders nearing their 10-year expiration. And? “Right before my event, my air pistol actually exploded,” said Lynda, managing a chuckle. “I had a minor panic, a mini-heart attack. I had to haul it over to the repair place. They put in some new parts and we were good to go.”

Lynda may be a carded athlete, but she doesn’t have a single sponsor.

Twice, she’s received a financial boost from CAN Fund (which, according to its website, is “giving people the opportunity to succeed. Our athletes compete for CANADA. Our CAN Fund Donors make sure they CAN.”)

Via Kids & Company, her family has had access to quality childcare.

“When you look at the cost of everything in that gun box, it can be a little staggering — but it’s also rewarding,” she said. “It’s like a capital investment. I know people who spend how much money on hockey equipment every year because their kids outgrow it.”

In some ways, Lynda can be unyielding.

In 2014, the Kiejkos’ first child was due shortly before the Commonwealth Games. Lynda, though, was determined to compete in Glasgow. Dorothy — who’d won gold at the 2011 Pan-Am Games in Guadalajara, Mexico, with a six-month-old baby at home — understood her sister’s mindset.

“She said, ‘You’re insane … but I’d be doing the same thing,'” said Lynda. “So I went with 15-day-old (Olivia) under my arm. I just snuck her everywhere. In retrospect, it was crazy. But everything worked out really, really well.”

For the 2020 Olympic trials, she lugged along her son, only three months old. When Logan was hungry, Lynda would scamper off the range, nurse him, run back in, keep training.

“My parents were that example for me — if you want to make something work, you find the ways,” she said. “If things don’t turn out the way you want, at least you tried. If things do turn out, even better.”

Finetuning for Tokyo meant frequent trips to the range, often after the kids were asleep. Maximizing her family hours, she used an electronic training system at home. To stay sharp, she also spent time dry-firing and visualizing.

“I don’t want to miss those opportunities — the bedtime stories, the hugs and kisses,” said Lynda. “I want to make sure I get all of those life moments.”

Off and, apparently, on the range. During the conversation, Lynda mentions that in Tokyo she’d competed alongside Georgia’s Nino Salukvadze, shooting at her ninth Olympics.

Which makes next question obvious — is Lynda taking aim at the 2024 Olympics? The answer will not surprise anyone who knows her.

“Yeah, I’m going to make a run for it,” said Lynda, who turned 41 two weeks ago. “If it works, fantastic — Paris, here I come. If not, it’s just going to be an incredible experience.

“I’ve got nothing to be ashamed of or shy about at this point. I mean, I’ve got three kids, a very successful engineering career, two Olympic Games under my belt. I’m pretty proud.”