Photos courtesy of Justine Bouchard, and University of Calgary Athletics Department.

By high school, Justine Bouchard had established herself. This was an all-around athlete, someone with a hand in the usual assortment of sports.

Soccer. Track and field. Swimming.

And then some.

In Grade 10, she played football — on the boys’ varsity team. “Which was super fun.” She ended up being named rookie of the year. “Not because I was the best player. I would just go out and work really hard and try to show those boys up at times.”

Away from the gridiron, Bouchard, strong and fast and determined, was becoming a dominating figure in the wrestling community. By the time she was named female athlete of the year at Wetaskiwin Composite High School, Canadian universities were circling.

Bouchard whittled the offers into a two-school shortlist — SFU and the University of Calgary because that’s where the best women wrestlers were gathered. “So I knew I would have good training partners and good quality coaching.”

Choosing to stay in her home province, close to family, she joined the Dinos program in 2004. Talking the other day about the decision-making process that led her to UCalgary, Bouchard said: “I definitely don’t regret it.”

Nor do the Dinos.

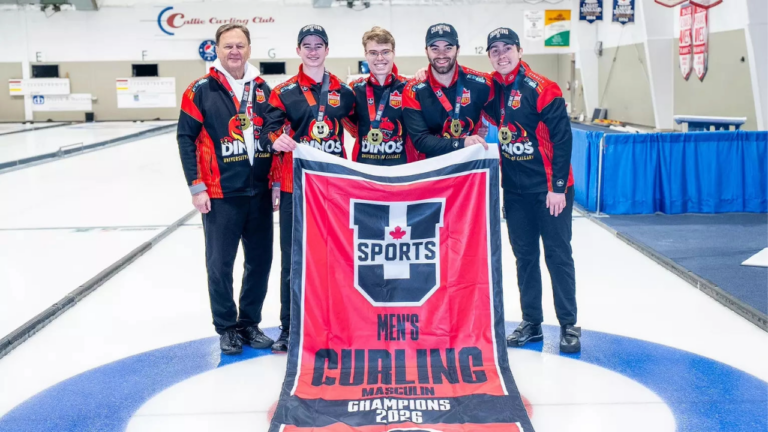

Because, while wearing red and gold, the 63-kilogram dynamo banked four Canada West conference titles, three national university crowns, and one world university championship.

Bouchard’s accomplishments did go beyond the campus and onto the international stage. But her five years in Calgary were remarkable — and sparkling enough to earn her a spot in the Dinos Hall of Fame.

Along with Lisa Harvey (track, cross-country), Paul Geddes (hockey), Peter Guterson (wrestling), George Kingston (hockey coach), Rick Coleman (builder), Bouchard is a member of the Class of 2022. They will be inducted in October.

She also happens to be the first female wrestler — but certainly not the last — to grace the Dinos’ shrine.

“Very cool,” said Bouchard, “especially since I feel I come from a strong group of women, especially in Calgary.”

With a laugh, she admits that she’d had a hunch something was up when her brother Charles began to text her, probing for tidbits about her wrestling career. “I’m like, ‘Well, that’s odd.’ He knew it would seem odd (to me), so he goes, ‘Don’t ask any questions.'”

A couple of months later, the call welcoming her to the Dinos Hall of Fame arrived. “Then it was, ‘So that’s what he was up to,'” she said, chuckling. “It was very exciting.”

Being recognized for an honour like this — she has also been inducted into the Wetaskiwin and County Sports Hall of Fame — is always a time of reflection.

“Honestly, I just feel so blessed that I’ve had the career I had,” said Bouchard, 36, “and all the amazing opportunities I’ve been given and all the experiences I’ve taken away.”

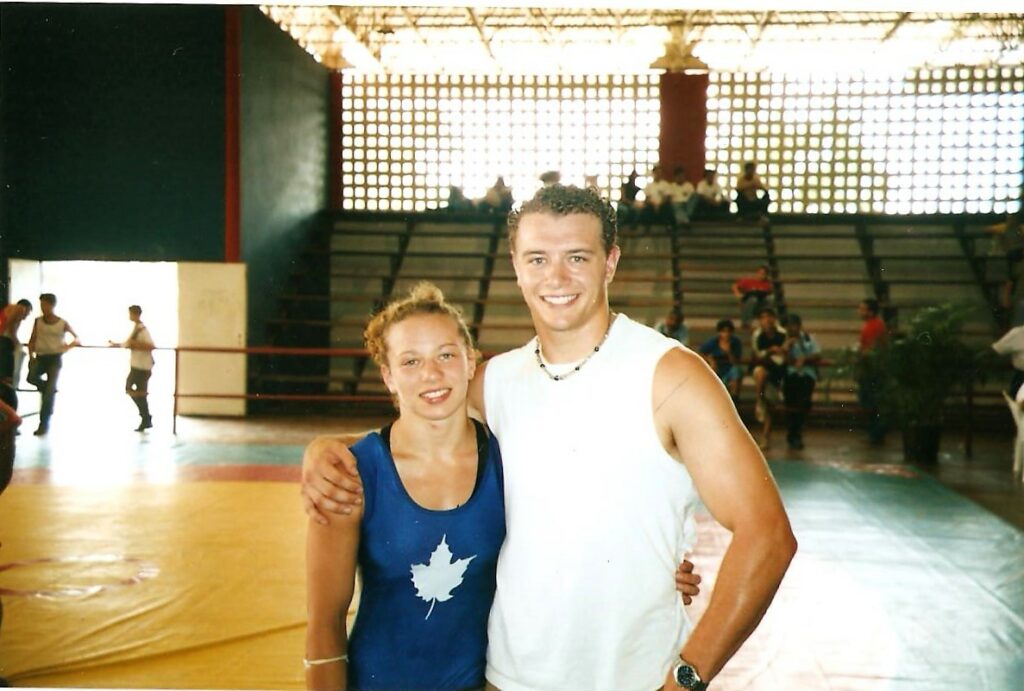

After graduating in 2009 with a biological sciences degree, Bouchard represented Canada, winning gold at the 2010 Commonwealth Games in New Delhi and the 2013 Pan-American Championships in Panama City.

But she often finds herself harkening back to the Dinos days, which she loved.

“Honestly, there’s no substitute for being on a varsity team,” she said. “You get extra matches going to different tournaments that were for only university wrestlers, then there’s the Canada West experience, where you really band together as a team, then compete against other teams. There’s no substitute for that. That’s a very, very fun experience when you’re working as a team even though you’re in an individual sport.

“That helped a lot, for sure, for development as a wrestler.”

A Calgary resident for 12 years, Bouchard retired in 2016 and now serves as assistant coach for the University of Alberta. This month, she’s coaching at the Canada Summer Games in Niagara, Ont.

As a leader, she brings to the mat a calm demeanour, which can provide a nice counter-balance to charged-up competitors. “A lot of the time, I consider myself more of a mentor. I feel that I can spread my knowledge.”

To her credit, there is plenty of hard-earned wisdom to share.

Even when asked to name a couple of career highlights — and there is plenty to choose from — Bouchard decides to rehash a loss at the Canadian trials leading into the 2012 Olympics in London.

That ordeal, she explains, prompted personal growth. “Definitely a big part of my wrestling career.”

Because of compressed weight classes — seven at international events, but only four for the Olympics — Bouchard had to tangle with Martine Dugrenier, the reigning world champion at 67 kilograms. After splitting the first two matches, Dugrenier prevailed in the third.

Bouchard’s dreams were dashed.

“I was very heartbroken,” she said. “I had a lot of my self-worth and identity tied into my winning and losing. So I kind of crumbled. Obviously, not a terrible downward spiral, but enough that I really recognized that I’m not happy and something needs to change.

“I even took a step back from the sport for a little bit, a couple months — ‘Maybe I’m done with this.’ But then every time I said that, I would just burst into tears. So it was, ‘You’re really not done. You’re just healing.’ It took a little while to be honest, but I finally did commit to the next cycle.”

For the 2016 trials, Bouchard was a different person, with a fresh mindset. The math this time had 10 national-team members trying to shoehorn into six weight classes for Rio.

She remembers well the approach the Canadians embraced in the lead-up: “Look, we’re all teammates. We’re all competitors. We just have to band together and decide that what every single person does in here to make themselves better is helping everyone to be better. And you have to celebrate in other people’s wins … because you’ve contributed to everyone’s success.”

Bouchard was totally on board. “I already considered myself a champion for having done everything I possibly could to get to that point. It was really powerful.” Which had been a departure from her disappointment in 2012 when, she says, there was a lack of maturity on her part. “Almost selfish, I guess,” said Bouchard. “I felt jaded, that people only care about you if you go to the Olympics. At that time, I cared if other people knew about what I had put in.

“Really, when I look back, that’s not what it’s about at all.”

It had been a junior high teacher who first encouraged Bouchard to try wrestling in Grade 7.

Her older brother Real was a high school grappler. The kid sister might also do well, thought the teacher, who brought the sport to Bouchard’s attention. The immediate reaction? “Isn’t wrestling for boys?”

But the teacher persisted, more than once nudging Bouchard towards wrestling. Eventually, she did make her way to practice. Soon after, she embraced the new sport.

“It was fun to try something and move your body in different ways,” said Bouchard, adding that progress on the mats was rewarding. “One of the first times I properly executed a move on someone who was trying to defend it, that was an instant blast of confidence.”

Particularly appealing was wrestling’s multi-faceted nature. You could be stronger or faster or more agile than your opponent. You could be more technical or tactical or possess a better mental game. “It’s very much a puzzle,” said Bouchard. “For every opponent, you have to put together difference pieces to be able to solve the puzzle.”

Using that approach, success began to mount.

Only two years into wrestling, she laid claim to gold at the 2000 Alberta Winter Games. She was just warming up.

Bouchard would go on to win 26 provincial titles and a dozen national crowns (two cadet, one juvenile, one junior, eight senior). At the university level, she ran the table, medalling at every conference championship, medalling at every national showdown, adding up to 10 medals in 10 appearances.

There was never a chance for Olympic glory — even being named the 2012 alternate didn’t get her to London — but she’s long made her peace with that.

“When I reflect, it’s still good to have strived to get those things,” said Bouchard. “You still become the best version of yourself. That’s really what it’s all about, anyway.”